Story One Our Place

A place of our own was the problem. Dad and Mom dreamed of one, saved for one and finally searched for one. They made it a family affair. Dad drove us to different places in our beautiful valley. We saw acres with streams running through, wild flowers blooming in soft green meadows, and pieces of rolling land with white birch trees and stately tamarack.

I loved the creeks. I wanted to sit with my feet stuck in the wet and listen to the water babbling over rocks. We looked for a long time, but for some reason didn't buy any of the wonderful pieces of land we explored.

"Girls, your mother and I bought our land," Dad announced one day.

My older sister, Norma and I clapped our hands and danced around. We even included Alan, our toddler brother, in the excitement. Now we could play in the creeks and fish and pick flowers.

When we drove to our place, I couldn't believe it. It was ten acres of completely flat sandy soil full of clump grass. The only trees were a few Poop Spruce and Bull Pine. Not that they aren't perfectly good trees, they just aren't pretty.

Dad moved an old L-shaped building on the front part of the acreage facing the highway and spent the next twenty-five years raising us kids and remodeling. He never quite finished anything. A piece of molding never got put on or a door was missing or the wallpaper border only on three walls.

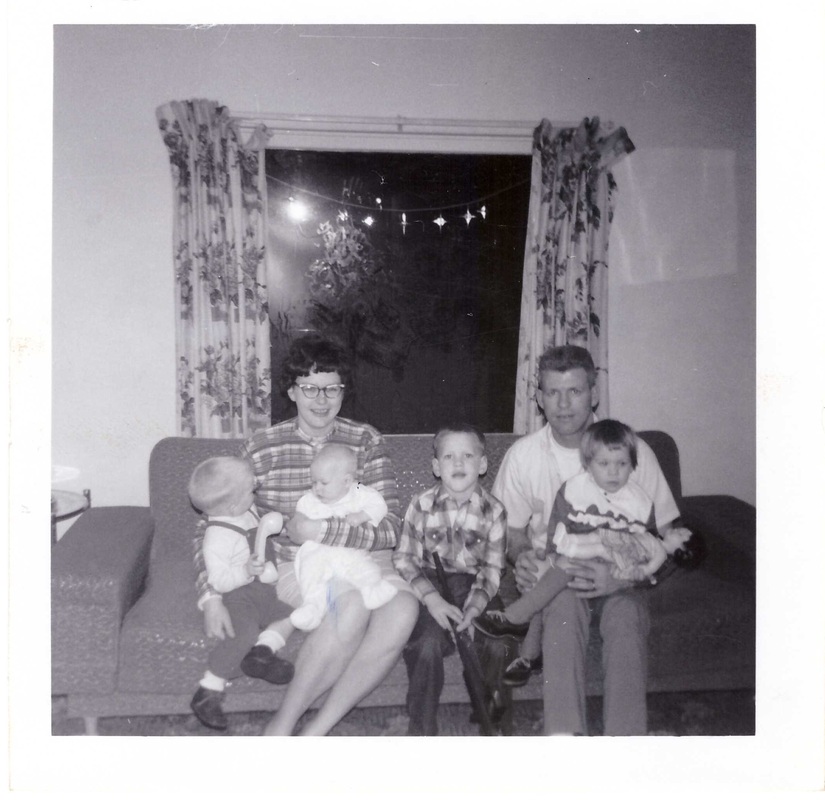

A small fiesty man, Dad tried to cover his crustiness with Christianity, but never quite succeeded. Things just plain aggravated him. He hated all surveyors, the Fish and Game Department, all politicians should be shot and us kids had better mind.

Mom, short and round, had a gentle soul. She loved her Lord, us kids and everyone around her. She also had the absolute knack of laying guilt on us heathen-like children. Two more were born after we moved onto the home place. There were now five heathenistic helluns to control and she let us run.

We covered a lot of territory.

Story two Magic Cape

One of the places we roamed was Grandpa Yeats farm. We had stayed there a lot before we got our own place, and it too belonged to us. We knew every inch of the creek bed, fields and buildings, the barn being our favorite.

One time when I was about four years old, Norma and I were swinging on our Tarzan swing in the hay loft. She was always Tarzan and I was always either Jane or Cheetah. She looked at me.

"I'm tired of this game," she said. "Wanna play Superman?"

"Sure," I answered.

"There are some old gunny sacks down by the grain bin. We could use them for magic capes to make us fly. Go get 'em."

Obedient, I climbed down the ladder and dug around in the dim light. I found two oat-smelling sacks. Norma tied one around her shoulders and helped me with mine.

"Now we can fly," she said.

I wasn't so sure.

She walked over to the hayloft door and gazed out onto the barn yard, then the far horizon. "I'll bet," she announced, "that we can fly right over the horse shed, the granary and the pig sty to the creek."

I looked where her finger pointed, then down. "I don't think I want to," I said. "You go first."

"No, I wouldn't want to leave you up here all by yourself."

Now this was my big sister who loved me dearly, and those words told me she also worried about me. Besides that she was two years older and knew everything. I stepped to the edge and stared. Way down.

"Don't be a chicken," said Norma. "You are Superman and can fly."

I flew. Down--yeah, down. The magic cape flew straight up around my neck. Splat. A manure pile saved my life. Our mother's face was very stressed as she washed me and put my arm in a sling.

I was secretly glad when Norma's place at the dinner table sat empty that evening.

A place of our own was the problem. Dad and Mom dreamed of one, saved for one and finally searched for one. They made it a family affair. Dad drove us to different places in our beautiful valley. We saw acres with streams running through, wild flowers blooming in soft green meadows, and pieces of rolling land with white birch trees and stately tamarack.

I loved the creeks. I wanted to sit with my feet stuck in the wet and listen to the water babbling over rocks. We looked for a long time, but for some reason didn't buy any of the wonderful pieces of land we explored.

"Girls, your mother and I bought our land," Dad announced one day.

My older sister, Norma and I clapped our hands and danced around. We even included Alan, our toddler brother, in the excitement. Now we could play in the creeks and fish and pick flowers.

When we drove to our place, I couldn't believe it. It was ten acres of completely flat sandy soil full of clump grass. The only trees were a few Poop Spruce and Bull Pine. Not that they aren't perfectly good trees, they just aren't pretty.

Dad moved an old L-shaped building on the front part of the acreage facing the highway and spent the next twenty-five years raising us kids and remodeling. He never quite finished anything. A piece of molding never got put on or a door was missing or the wallpaper border only on three walls.

A small fiesty man, Dad tried to cover his crustiness with Christianity, but never quite succeeded. Things just plain aggravated him. He hated all surveyors, the Fish and Game Department, all politicians should be shot and us kids had better mind.

Mom, short and round, had a gentle soul. She loved her Lord, us kids and everyone around her. She also had the absolute knack of laying guilt on us heathen-like children. Two more were born after we moved onto the home place. There were now five heathenistic helluns to control and she let us run.

We covered a lot of territory.

Story two Magic Cape

One of the places we roamed was Grandpa Yeats farm. We had stayed there a lot before we got our own place, and it too belonged to us. We knew every inch of the creek bed, fields and buildings, the barn being our favorite.

One time when I was about four years old, Norma and I were swinging on our Tarzan swing in the hay loft. She was always Tarzan and I was always either Jane or Cheetah. She looked at me.

"I'm tired of this game," she said. "Wanna play Superman?"

"Sure," I answered.

"There are some old gunny sacks down by the grain bin. We could use them for magic capes to make us fly. Go get 'em."

Obedient, I climbed down the ladder and dug around in the dim light. I found two oat-smelling sacks. Norma tied one around her shoulders and helped me with mine.

"Now we can fly," she said.

I wasn't so sure.

She walked over to the hayloft door and gazed out onto the barn yard, then the far horizon. "I'll bet," she announced, "that we can fly right over the horse shed, the granary and the pig sty to the creek."

I looked where her finger pointed, then down. "I don't think I want to," I said. "You go first."

"No, I wouldn't want to leave you up here all by yourself."

Now this was my big sister who loved me dearly, and those words told me she also worried about me. Besides that she was two years older and knew everything. I stepped to the edge and stared. Way down.

"Don't be a chicken," said Norma. "You are Superman and can fly."

I flew. Down--yeah, down. The magic cape flew straight up around my neck. Splat. A manure pile saved my life. Our mother's face was very stressed as she washed me and put my arm in a sling.

I was secretly glad when Norma's place at the dinner table sat empty that evening.

Story 3 Pay Back

By the time we were in the fourth and sixth grades Norma was a complete through and through tomboy and the controller of the neighborhood. Norma-nator should have been her name. Always meek and shy, I drove her out of her mind.

We didn't lack for playmates. Next door in a long green stucco house lived the Grilley boys, across the highway was the Nelsons. They were old, but their granddaughter played with us when she visited. The three Horner girls lived on the other side and on top of Saurey Hill lived the Saureys. This bunch of kids is who we played with or fought with depending on Norma's mood for the day.

We had my wish. A creek was only a half mile away. We followed a country road north until we came to a spot where the creek passed under the road, made a bend and went back under the road. This area was ours. We fished and swam, built forts and ate picnic lunches there.

Shy Brookies lived in that stream. We caught them on worms and Schnell hooks, size number six. We crept real careful, not making a sound or casting a shadow on the water, as we flung our lines into the water. The current took the worms downstream under overhanging bushes where fish hid.

Norma caught her share as we all did, but woe be to any of us who made noise. One day Norma shrieked. She high-stepped quickly in the opposite direction. "What's the matter?" I asked in a loud whisper. "You're scaring the fish."

"I almost stepped on a damn snake," she answered.

"Not afraid of a little snake are you?" I asked, surprised at her forbidden word.

"Of course not! I just don't like them."

Norma is afraid of the small green water snakes, my mind said. This was an enormous discovery! I now had an equalizer!

I bided my time. Sure enough a few days later she told me to move further downstream, because I was in the particular spot she wanted.

Mumbling to myself, I trudged downstream and plopped on the bank. Movement caught my eye. I reached into the weeds and pulled out a wiggling, hissing snake. It was only a small water snake, but when I held it by the back of the neck, it dangled down a good foot. Wiggling. Mouth open and forked tongue sticking out. Perfect.

"See what I found," I said as I quietly stood at her squatting back.

She glanced up and saw what I held. "Yukkkk," she screamed. "Get away!"

I held it closer.

"Wait till I tell Mom what you did!" she screamed at me and ran for home.

A little guilt should have nagged at my mind, but fishing was good that day.

Story 4 Diving Boards

The bend in the creek made a great swimming hole. Kids being kids, we were not satisfied with jumping off the bank. Therefore, we spent hours building diving boards of various sizes and shapes. The engineering of these magnificent boards was something to see.

One of the benefits of Dad working in a sawmill was that he brought home scraps and pieces of lumber. He supplied us with us old lumber for our projects. One day he even gave us a plank.

Our cousins from Kalispell were visiting. They spent a lot of time at our house in the summer. Jeanie, Bernie and Lyle were a shade older and very sophisticated. They were town kids. Bernie and Lyle lugged the plank the half mile to the creek. We built up the bank with the clay, making it as high as we dared and plenty wide enough to hold the plank. We placed it just prefect with one end sticking out over the water.

We pile lots of rocks. Some were boulders, on the other end to hold it in place. After many hours and much labor our supreme board was completed.

Norma was the only one whoever got to make a dive off the boards we made. She was the biggest, and it fell to her to be the test diver. If the board held up for her, then anyone of us could use it in relative safety. We watched from the bank as diving board after diving board fell into the water with great splashes of water when Norma jumped off.

This board was no different.

"We should get to go first," said Bernie and Lyle. "We lugged the plank to the creek."

Norma gave them the evil eye.

"All right," said Bernie, "we'll watch for weak spots in the rocks."

Norma took her time. She inched her way out onto the board. She jiggled it up and down.

"Any weak spots," she asked.

"Naw," answered Bernie.

Norma sprang in the air. Her feet came down on the board for a mighty lift off. It buckled, sending rocks and boulders high. Norma hit the water with a belly flop that shook the earth and sent a spray of water arcing over us. Her scream is what I remember. Never heard one like it again. I wondered how she avoided getting killed and going to heaven.

By the time we were in the fourth and sixth grades Norma was a complete through and through tomboy and the controller of the neighborhood. Norma-nator should have been her name. Always meek and shy, I drove her out of her mind.

We didn't lack for playmates. Next door in a long green stucco house lived the Grilley boys, across the highway was the Nelsons. They were old, but their granddaughter played with us when she visited. The three Horner girls lived on the other side and on top of Saurey Hill lived the Saureys. This bunch of kids is who we played with or fought with depending on Norma's mood for the day.

We had my wish. A creek was only a half mile away. We followed a country road north until we came to a spot where the creek passed under the road, made a bend and went back under the road. This area was ours. We fished and swam, built forts and ate picnic lunches there.

Shy Brookies lived in that stream. We caught them on worms and Schnell hooks, size number six. We crept real careful, not making a sound or casting a shadow on the water, as we flung our lines into the water. The current took the worms downstream under overhanging bushes where fish hid.

Norma caught her share as we all did, but woe be to any of us who made noise. One day Norma shrieked. She high-stepped quickly in the opposite direction. "What's the matter?" I asked in a loud whisper. "You're scaring the fish."

"I almost stepped on a damn snake," she answered.

"Not afraid of a little snake are you?" I asked, surprised at her forbidden word.

"Of course not! I just don't like them."

Norma is afraid of the small green water snakes, my mind said. This was an enormous discovery! I now had an equalizer!

I bided my time. Sure enough a few days later she told me to move further downstream, because I was in the particular spot she wanted.

Mumbling to myself, I trudged downstream and plopped on the bank. Movement caught my eye. I reached into the weeds and pulled out a wiggling, hissing snake. It was only a small water snake, but when I held it by the back of the neck, it dangled down a good foot. Wiggling. Mouth open and forked tongue sticking out. Perfect.

"See what I found," I said as I quietly stood at her squatting back.

She glanced up and saw what I held. "Yukkkk," she screamed. "Get away!"

I held it closer.

"Wait till I tell Mom what you did!" she screamed at me and ran for home.

A little guilt should have nagged at my mind, but fishing was good that day.

Story 4 Diving Boards

The bend in the creek made a great swimming hole. Kids being kids, we were not satisfied with jumping off the bank. Therefore, we spent hours building diving boards of various sizes and shapes. The engineering of these magnificent boards was something to see.

One of the benefits of Dad working in a sawmill was that he brought home scraps and pieces of lumber. He supplied us with us old lumber for our projects. One day he even gave us a plank.

Our cousins from Kalispell were visiting. They spent a lot of time at our house in the summer. Jeanie, Bernie and Lyle were a shade older and very sophisticated. They were town kids. Bernie and Lyle lugged the plank the half mile to the creek. We built up the bank with the clay, making it as high as we dared and plenty wide enough to hold the plank. We placed it just prefect with one end sticking out over the water.

We pile lots of rocks. Some were boulders, on the other end to hold it in place. After many hours and much labor our supreme board was completed.

Norma was the only one whoever got to make a dive off the boards we made. She was the biggest, and it fell to her to be the test diver. If the board held up for her, then anyone of us could use it in relative safety. We watched from the bank as diving board after diving board fell into the water with great splashes of water when Norma jumped off.

This board was no different.

"We should get to go first," said Bernie and Lyle. "We lugged the plank to the creek."

Norma gave them the evil eye.

"All right," said Bernie, "we'll watch for weak spots in the rocks."

Norma took her time. She inched her way out onto the board. She jiggled it up and down.

"Any weak spots," she asked.

"Naw," answered Bernie.

Norma sprang in the air. Her feet came down on the board for a mighty lift off. It buckled, sending rocks and boulders high. Norma hit the water with a belly flop that shook the earth and sent a spray of water arcing over us. Her scream is what I remember. Never heard one like it again. I wondered how she avoided getting killed and going to heaven.

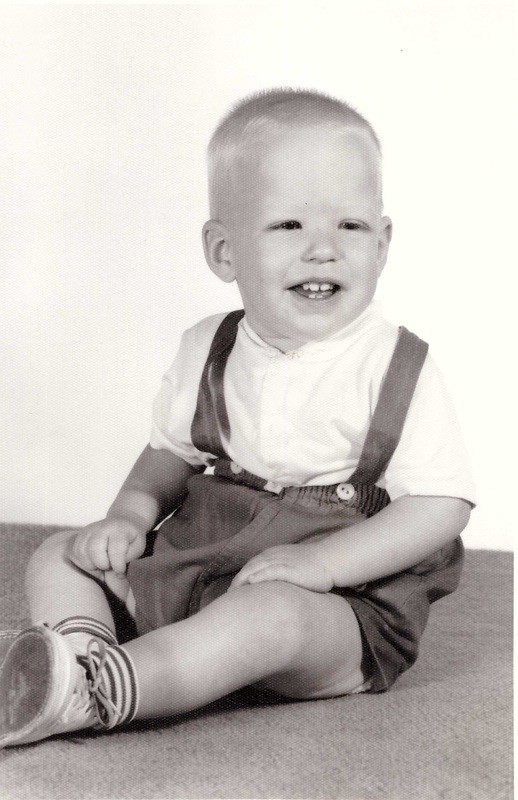

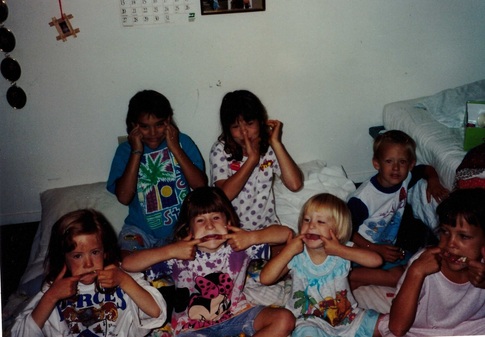

These kids are the Connor cousins we played with. Bernie is the second from the front and helped build the diving boards and scared Sister Rachael half to death with a snake. Jeanie, his sister is the back one and she was always in on all the evil deeds.

Back left to right

Marie, Alan, Norma

Doris and David

Back left to right

Marie, Alan, Norma

Doris and David

Story 5 Our Souls

Before we joined the Baptist Church, Mom sent us kids to a little white church in Columbia Falls. It was a Pentecostal Church of God. The pastor was Brother Arthur, his wife was Sister Mabel, and Mable's sister, was Sister Rachel. These were fine reserved people, who put up with us kids for the sake of our souls.

They lived near Fortine on a Christmas tree farm isolated in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. A main cabin and several small cabins for bunk houses served for their living quarters. I can close my eyes and see it plain as day; the hilly land around the cabins cleared of timber, small brush covered the ground, and muddy clay soil.

Brother Arthur invited us kids to stay for several weeks in the summertime. Us kids included Jeanie, Bernie, Norma and myself. We had great fun up there, way out in the boon docks. Creek fishing was the top priority. We caught many small Brookies and Sister Mable fried them for us.

Other wildlife abounded, like pine squirrels and fat gophers, whitetail deer, and blue birds. And snakes. The ones we spotted slithering near rocks or rushing in the weeds along the creek banks were only small garter snakes, but one in particular caused such a commotion you would not believe.

Norma, Bernie and Jeanie spied this snake down by a big mud puddle, warming itself on the hot clay. With nothing better to do they decided to see if they could kill it with mud clods, which were rock hard.

I innocently stood by and watched the three of them throw missiles until Bernie finally clunked it hard enough that it died. Dead. Didn't move.

Norma poked it with a stick. "Yep it's breathed its last on this here earth. Ya know, Sister Rachel is scared of snakes. Bet she'd be glad we killed one."

"Bet she would," agreed Bernie.

"Should we show her?" asked Jeanie. "Who's going to pick it up?"

Norma shook her head, plump pigtails waving. "I'm not scared of them anymore, but I'm not touching its scaley skin." She jiggled her shoulders as if freeing the thought.

"Oh you babies," said Bernie. "I'll do it." He got a long stick and picked the snake up, dangling it in the middle. We all marched to the main cabin where Sister Rachel and Sister Mabel fixed food.

Bernie, Jeanie and Norma traipsed into the cabin, "Look what we got." About that time the snake decided it was not dead and wiggled off the stick! I was standing back and could barely see what happened. Norma screamed at the top of her lungs, Jeanie ran toward the door, Sister Mabel stood on a chair, Sister Rachel was practically in a dead faint standing on the couch. On his hand and knees, Bernie tried to catch the snake, who slithered this way and that trying very hard to get away.

Screeching and screaming erupted, enough to bring the roof down! Bernie finally caught the poor thing and carried it outside.

Sister Rachel slumped down on the couch. Her long brown hair hung around her bent head. "I just can't believe it," she repeated several times to no one in particular. Her stress showed around her white pinched lips. She had a little trouble with forgiveness that day.

Brother Arthur and Sister Mable moved on, and we weren't attending a church. Mom wanted us kids to hear the word of the Lord and by gum we were going to go. She convinced Dad that we should join the First Baptist Church and go as a family.

I remember the day Dad was baptized. He got dunked in Lake Blaine by Pastor Warner. It was a grand day for my parents. They were very happy.

Our family became churchie.

Before we joined the Baptist Church, Mom sent us kids to a little white church in Columbia Falls. It was a Pentecostal Church of God. The pastor was Brother Arthur, his wife was Sister Mabel, and Mable's sister, was Sister Rachel. These were fine reserved people, who put up with us kids for the sake of our souls.

They lived near Fortine on a Christmas tree farm isolated in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. A main cabin and several small cabins for bunk houses served for their living quarters. I can close my eyes and see it plain as day; the hilly land around the cabins cleared of timber, small brush covered the ground, and muddy clay soil.

Brother Arthur invited us kids to stay for several weeks in the summertime. Us kids included Jeanie, Bernie, Norma and myself. We had great fun up there, way out in the boon docks. Creek fishing was the top priority. We caught many small Brookies and Sister Mable fried them for us.

Other wildlife abounded, like pine squirrels and fat gophers, whitetail deer, and blue birds. And snakes. The ones we spotted slithering near rocks or rushing in the weeds along the creek banks were only small garter snakes, but one in particular caused such a commotion you would not believe.

Norma, Bernie and Jeanie spied this snake down by a big mud puddle, warming itself on the hot clay. With nothing better to do they decided to see if they could kill it with mud clods, which were rock hard.

I innocently stood by and watched the three of them throw missiles until Bernie finally clunked it hard enough that it died. Dead. Didn't move.

Norma poked it with a stick. "Yep it's breathed its last on this here earth. Ya know, Sister Rachel is scared of snakes. Bet she'd be glad we killed one."

"Bet she would," agreed Bernie.

"Should we show her?" asked Jeanie. "Who's going to pick it up?"

Norma shook her head, plump pigtails waving. "I'm not scared of them anymore, but I'm not touching its scaley skin." She jiggled her shoulders as if freeing the thought.

"Oh you babies," said Bernie. "I'll do it." He got a long stick and picked the snake up, dangling it in the middle. We all marched to the main cabin where Sister Rachel and Sister Mabel fixed food.

Bernie, Jeanie and Norma traipsed into the cabin, "Look what we got." About that time the snake decided it was not dead and wiggled off the stick! I was standing back and could barely see what happened. Norma screamed at the top of her lungs, Jeanie ran toward the door, Sister Mabel stood on a chair, Sister Rachel was practically in a dead faint standing on the couch. On his hand and knees, Bernie tried to catch the snake, who slithered this way and that trying very hard to get away.

Screeching and screaming erupted, enough to bring the roof down! Bernie finally caught the poor thing and carried it outside.

Sister Rachel slumped down on the couch. Her long brown hair hung around her bent head. "I just can't believe it," she repeated several times to no one in particular. Her stress showed around her white pinched lips. She had a little trouble with forgiveness that day.

Brother Arthur and Sister Mable moved on, and we weren't attending a church. Mom wanted us kids to hear the word of the Lord and by gum we were going to go. She convinced Dad that we should join the First Baptist Church and go as a family.

I remember the day Dad was baptized. He got dunked in Lake Blaine by Pastor Warner. It was a grand day for my parents. They were very happy.

Our family became churchie.

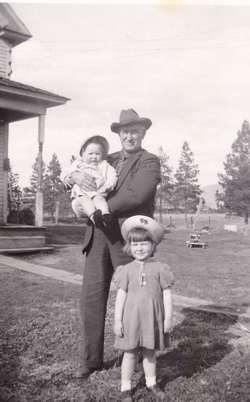

Grandpa Yeats, Norma and me

Grandpa Yeats, Norma and me

Story 6 Ice Cream

Bars

Grandpa Yeats, a tall straight man, looked exactly what a farmer should in his bibbed overalls and straw work hat. His chest barreled under wide shoulders, and his hair was white with a bald top. He smiled the kindest smile I ever saw. His patience with farm animals and grandchildren was eternal.

As my sister Norma and I roamed all over the two-hundred acre farm with Charmall, his daughter from a second marriage, we knew he was always there tending the animals or fields or buildings. We just gave a yell and his answering call guided us to where he worked. We played by ourselves for hours on end, but never felt alone.

Grandpa set very few limits on us as we traveled between the creek and the farm buildings seeking to entertain ourselves. His only real no-no was not to ride the calves. This bugged Norma as all forbidden things did.

We were at the farm one evening for milking and were instructed to feed the calves. We filled the galvanized nursing buckets with foamy warm milk and carried them through the barn to the slat and wire gate of the calf pen.

"I'm gonna ride one of the calves," Norma whispered to me.

"No," I whispered back, "You hadn't better. Grandpa told us never to do that."

"Oh, you sissy. You never want to do anything, besides he'll never know unless you squeal on me." Her eyes dared me to try and tell anything on her. "You can hold it's head while I get on."

We set our buckets down carefully because we knew better to get dirt on the rubber nipple or to spill any milk. Norma slid back the handle and opened the gate.

I dipped my fingers into the milk and held them toward the nearest calf. His perfectly white face leaned to the smell of milk and he came nearer. Quickly I grabbed him around the neck and held on for dear life while Norma straddled his back.

I let go.

The calf's eyes glazed in panic, his body quivered and his sturdy legs trembled. Norma kicked him in the ribs and held one hand high in the air. The calf jumped straight up arching it's back, then fish-tailed coming down at full speed. He tore around the pen. Norma landed seat first on the mucky ground.

"What are you girls doing?" asked Grandpa's stern voice. Instantaneously we jumped, then held down our heads. "Both of you go home right now!"

"I'm sorry, Grandpa," I said as we passed by.

"Sorry doesn't help that calf one bit." He picked up the bucket and came into the pen holding the gate open for us to leave. And we did. We scurried through the barn yard, down the lane, across LaSalle Highway and onto our gravel road.

The two-mile walk home stretched ahead, but neither of us felt in any hurry to get there. I for sure didn't want Norma to tell Mom what we did.

"Are you going to tell Mom?" I asked.

"Are you nuts, of course not?"

"What if Grandpa tells her?"

"He won't."

I wasn't so sure. He seemed awfully mad. We followed the road around a bend, up a short hill, past Westry's farm, then by the Catholic cemetery and to the back part of our ten acres. The sun sank below Dollar Hill as we ran the length of our property through clump grass and alfalfa and into the house. Mom was setting the table when we arrived.

"I thought you were spending the night with Charmall in the barn," she said.

"Naw," answered Norma, "we decided not to."

"I see," said Mom.

The next day Grandpa's old farm truck pulled into our yard and I knew we were dead, but he only wanted to know if we were going to ride into Whitefish with him for the weekly cream delivery. Norma and I climbed into the back of his old truck joining, Charmall and her sister. The ten miles of asphalt sped by as we hung on tight with wind blowing in our faces. We were going to town.

The creamery, a clean white place, smelled like cream or ice cream I should say. Grandpa always bought us kids an ice cream bar. And he did that day too even after our crime, never once mentioning it. The ice cream tasted even more wonderful.

When we got home, I found Mom in the garden hoeing the carrots.

"Mom," I said, "Norma rode one of Grandpa's calves yesterday and I helped her."

"What did Grandpa say?" Mom straightened and looked at me.

"He just told us to go home, but I could tell he was really mad."

"Did you tell him you were sorry?"

"Yes, but he said sorry didn't do the calf any good."

"Did it?"

I shook my head. "I couldn't believe he came for us. He even bought us an ice cream bar just like always."

"Honey," said Mom, "you know your grandfather loves you kids. When someone loves you, they don't stay mad."

Story 7 Lost and Found

Cancer is such an awful word. I was in the fifth grade when I learned it. My wonderful Grandpa Yeats had cancer. It started with a sore on his lip that never healed. It spread down his throat and killed him.

On the day Mom allowed me to visit him, I slipped quietly inside his bedroom and stood gaping at him. My big powerful grandfather had shriveled to skin and bones. He moaned from pain. I blinked several times as I stared.

His eyes fluttered, then opened. They were haunted with pain as he stared back at me. He reached out his thin white arm and tried to grab my skirt. He missed by just a little.

"Get me a knife," he said, in a voice I could barely hear. He said it again.

I fled to Mom.

"Grandpa wants me to bring him a knife."

"Oh, Honey." Mom sighed and silently spoke to me with her eyes.

"What does he want it for?" I asked.

"He is out of his mind with pain and don't you ever take him one."

Grandpa died in the dry-hot summer. We buried him in his cemetery plot just up the highway from our house. He had bought a six-person plot, and right smack dab in the center was a giant Bull Pine tree. A man's tree. Sturdy trunk, strong branches and large tufts of long pine needles for muscles.

Grandpa's tombstone sat at the base of the tree, leaning toward it, as if trying to draw life from it. I used to sit under that tree and wile away the hours, contemplating life and who had done what to me. The cemetery was wild and overgrown. No mowed grass or sprinklers. A perfect spot.

I would run my fingers through the dry, sandy soil piling it into little mounds for foundations for the dry pine needle houses I built. Then I would brush away the needles and carefully pat it all smooth again. Planted in that sandy soil were two strong enduring forces, the roots of the tree and the roots of my family.

Grandpa Yeats, a tall straight man, looked exactly what a farmer should in his bibbed overalls and straw work hat. His chest barreled under wide shoulders, and his hair was white with a bald top. He smiled the kindest smile I ever saw. His patience with farm animals and grandchildren was eternal.

As my sister Norma and I roamed all over the two-hundred acre farm with Charmall, his daughter from a second marriage, we knew he was always there tending the animals or fields or buildings. We just gave a yell and his answering call guided us to where he worked. We played by ourselves for hours on end, but never felt alone.

Grandpa set very few limits on us as we traveled between the creek and the farm buildings seeking to entertain ourselves. His only real no-no was not to ride the calves. This bugged Norma as all forbidden things did.

We were at the farm one evening for milking and were instructed to feed the calves. We filled the galvanized nursing buckets with foamy warm milk and carried them through the barn to the slat and wire gate of the calf pen.

"I'm gonna ride one of the calves," Norma whispered to me.

"No," I whispered back, "You hadn't better. Grandpa told us never to do that."

"Oh, you sissy. You never want to do anything, besides he'll never know unless you squeal on me." Her eyes dared me to try and tell anything on her. "You can hold it's head while I get on."

We set our buckets down carefully because we knew better to get dirt on the rubber nipple or to spill any milk. Norma slid back the handle and opened the gate.

I dipped my fingers into the milk and held them toward the nearest calf. His perfectly white face leaned to the smell of milk and he came nearer. Quickly I grabbed him around the neck and held on for dear life while Norma straddled his back.

I let go.

The calf's eyes glazed in panic, his body quivered and his sturdy legs trembled. Norma kicked him in the ribs and held one hand high in the air. The calf jumped straight up arching it's back, then fish-tailed coming down at full speed. He tore around the pen. Norma landed seat first on the mucky ground.

"What are you girls doing?" asked Grandpa's stern voice. Instantaneously we jumped, then held down our heads. "Both of you go home right now!"

"I'm sorry, Grandpa," I said as we passed by.

"Sorry doesn't help that calf one bit." He picked up the bucket and came into the pen holding the gate open for us to leave. And we did. We scurried through the barn yard, down the lane, across LaSalle Highway and onto our gravel road.

The two-mile walk home stretched ahead, but neither of us felt in any hurry to get there. I for sure didn't want Norma to tell Mom what we did.

"Are you going to tell Mom?" I asked.

"Are you nuts, of course not?"

"What if Grandpa tells her?"

"He won't."

I wasn't so sure. He seemed awfully mad. We followed the road around a bend, up a short hill, past Westry's farm, then by the Catholic cemetery and to the back part of our ten acres. The sun sank below Dollar Hill as we ran the length of our property through clump grass and alfalfa and into the house. Mom was setting the table when we arrived.

"I thought you were spending the night with Charmall in the barn," she said.

"Naw," answered Norma, "we decided not to."

"I see," said Mom.

The next day Grandpa's old farm truck pulled into our yard and I knew we were dead, but he only wanted to know if we were going to ride into Whitefish with him for the weekly cream delivery. Norma and I climbed into the back of his old truck joining, Charmall and her sister. The ten miles of asphalt sped by as we hung on tight with wind blowing in our faces. We were going to town.

The creamery, a clean white place, smelled like cream or ice cream I should say. Grandpa always bought us kids an ice cream bar. And he did that day too even after our crime, never once mentioning it. The ice cream tasted even more wonderful.

When we got home, I found Mom in the garden hoeing the carrots.

"Mom," I said, "Norma rode one of Grandpa's calves yesterday and I helped her."

"What did Grandpa say?" Mom straightened and looked at me.

"He just told us to go home, but I could tell he was really mad."

"Did you tell him you were sorry?"

"Yes, but he said sorry didn't do the calf any good."

"Did it?"

I shook my head. "I couldn't believe he came for us. He even bought us an ice cream bar just like always."

"Honey," said Mom, "you know your grandfather loves you kids. When someone loves you, they don't stay mad."

Story 7 Lost and Found

Cancer is such an awful word. I was in the fifth grade when I learned it. My wonderful Grandpa Yeats had cancer. It started with a sore on his lip that never healed. It spread down his throat and killed him.

On the day Mom allowed me to visit him, I slipped quietly inside his bedroom and stood gaping at him. My big powerful grandfather had shriveled to skin and bones. He moaned from pain. I blinked several times as I stared.

His eyes fluttered, then opened. They were haunted with pain as he stared back at me. He reached out his thin white arm and tried to grab my skirt. He missed by just a little.

"Get me a knife," he said, in a voice I could barely hear. He said it again.

I fled to Mom.

"Grandpa wants me to bring him a knife."

"Oh, Honey." Mom sighed and silently spoke to me with her eyes.

"What does he want it for?" I asked.

"He is out of his mind with pain and don't you ever take him one."

Grandpa died in the dry-hot summer. We buried him in his cemetery plot just up the highway from our house. He had bought a six-person plot, and right smack dab in the center was a giant Bull Pine tree. A man's tree. Sturdy trunk, strong branches and large tufts of long pine needles for muscles.

Grandpa's tombstone sat at the base of the tree, leaning toward it, as if trying to draw life from it. I used to sit under that tree and wile away the hours, contemplating life and who had done what to me. The cemetery was wild and overgrown. No mowed grass or sprinklers. A perfect spot.

I would run my fingers through the dry, sandy soil piling it into little mounds for foundations for the dry pine needle houses I built. Then I would brush away the needles and carefully pat it all smooth again. Planted in that sandy soil were two strong enduring forces, the roots of the tree and the roots of my family.

Grandma Lizzy

Grandma Lizzy

Story 8, Green

Beans

The summer Grandpa died, I found a grandma. My father's family planned a reunion at the home ranch and we were going. Finally, I would get to meet my Grandma Lizzy. I saw her a couple of times when I was little, but that didn't count. Both my best friends, Barb and Rose had really neat grandmas and I didn't have any that I knew.

We packed the old chevy full of stuff seven people needed for a four-day weekend and began the two-hundred mile trip east through the Rocky Mountains on a narrow curving road.

We traveled around the Devil's Elbow, across the Continental Divide, down into the Blackfoot Indian Reservation at Browning, then on across the high-line of northern Montana. At Rudyard, we turned north toward the Canadian border and the isolated homestead where Dad was raised.

Norma and I were all excited about going to the ranch and seeing all the cousins. I didn't know I had so many. When we got out of the car, they were everywhere. An amazing amount of people with the bond of blood.

Friendly and outgoing, Norma fit right in with them. I was shy. She was strong, stocky, and dark rich in coloring. I was willowy, dishwater blonde and freckled. She was handsome and I was only ordinary.

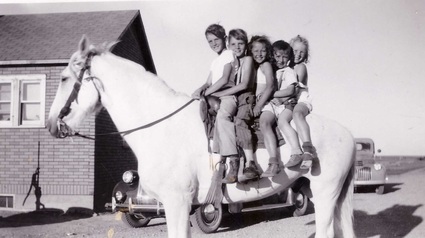

The ranch house sat on flat land above deep coolies where the Milk River wound it's way through their bottom separating the ranch from Canada. With a beauty all their own, sage brush, clump grass, and low flat cacti covered the ground, all either tan or brown.

The next morning I overheard Norma and the older cousins planning a horse riding expedition and I wanted to go.

"No," said Norma, "you are way too young to ride the ranch horses." That settled that. Her word was law. I sat by myself on the porch step and watched them ride by laughing and excited as they guided their horse down the narrow trail to the bottom of the coolies.

I went inside and found Grandma Lizzy in her kitchen. This, my only living grandma, was strange to me. She was short, wide and walked with a limp. A hearing-aid poked in her ear had a wire running down inside the neck of her gingham house dress, and she smelled old. I liked her friendly smile.

"I could use someone to chat with," she said. "Sit down and snap those green beans for me." I looked at the dish pan filled with beans and obeyed.

"Grandma Lizzy," I asked as my pile of snapped beans grew on the table, "is it really true you had a hamburger stand?"

"Um-hum."

"Out here on the prairies?"

Her pale blue eyes searched my hazel ones as she nodded.

"Yep," she said, "I did. It was back in '28, '29 and '30 that your grandpa put on a rodeo every forth of July."

"A rodeo?"

"Yep, he invited people from all around. They came by the cars full. Pa had them park in a big circle. That made a nice arena. He provided the bucking horses and steers for roping."

"Why did he do it?"

"To earn cash money." She tilted slightly back on her maple chair. Her face lined with a mole on her chin. It had a coarse center hair. She seemed tired as she continued, "We did everything we could to earn it."

"Tell me about the hamburger stand."

Her eyes twinkled. "First, I'd butcher me a cow, grind the whole thing into hamburger to make patties. I took them to Goldstone on the day of the rodeo, set up my stand next to Warhank's store so I could have electricity for the hot plates"

"Where did you get the stand?"

"The boys made it. The front was open -- you know, like the firecracker stands are. They made it just big enough for me and my cooking things. I sold the hamburgers for twenty-five cents each. I made good cash money, but let me tell you it was hard hot work inside that stand and the horse flies were awful. Sometimes I wonder how I did it."

I looked at that tiny old lady and wondered too, but then her eyes held mine tight and I knew. Those eyes still held the fiestyness of her youth. My dad had the same eyes.

"Who rode the bucking horses?"

"Cow hands and Indians from the Rocky Boy Reservation. Those indians could really ride those bucking broncos. My boys, Donald and Laverne, could ride 'em real good too."

I pushed my pile of snapped beans further into the middle of the table to make room for more. From the dish pan, I poured Grandma Lizzy another lap full and refilled my lap.

"Did you have Fourth of July fireworks for the rodeo?" I picked up another bean with my tired fingers.

"No, we just had bucking horses and drunken Indians."

I blinked. Nobody ever mentioned drunken anything to me before so naturally I asked, "How'd they get drunk?"

"I'm not sure," she said. "Could be that Pa sold them some Canadian beer." She paused and rubbed her nose. "The border patrolman checked on Pa every chance he got to see if he could catch Pa with bootleg beer or whiskey, but he never found it. Every now and then he stopped by when it was late in the day and spend the night. He always hung his gun on the front porch before coming into the house. I always gave him a good supper with a big glass of cold buttermilk. He loved my buttermilk. The next morning he would continue on his way, patrolling the district and snooping in folk's business."

She snapped a few beans while thinking.

"One time he caught your Uncle Cecil pelting beavers and confiscated all twenty of them. That made me darn mad. The hide money would have bought winter shoes for the kids."

Grandma Lizzy's face set in a hard line. "I fed him good, and he paid me back by poking his nose in everywhere. Always checking for bootleg whiskey, then he found them turkeys."

"Turkeys?"

"Thirty dressed turkeys cost Pa his brand new 1936 Ford pickup."

"What?"

"Yep, thirty turkeys caused a great commotion. I told you old man Warhank owned the store in Goldstone?"

I nodded.

"He wanted Pa to pick up thirty dressed turkeys and bring them over the border for him. Warhank wanted to sell them in the store and everything was just fine until that nosy border patrolman happened into the store. He demanded to know where the turkeys came from. We figured Warhank squealed on Pa to get himself off the hook."

"That wasn't very nice," I interrupted.

"No, it wasn't. When the border patrolman showed up at the ranch, he told us he had to confiscate our brand new 1936 Ford pickup, because it transported illegal turkeys. I hit the ceiling. I went out and got in the pickup. I flat told him that nobody was taking my pickup anywhere. I paid seven hundred cash dollars for it, and NOBODY IS TAKING IT ANYWHERE!"

I stared at my grandmother

Fire and anger crackled in her eyes. "The border patrolman ended up with the pickup. Pa ended up with a very mad wife, and old man Warhank ended up Scott free."

A chuckle grew in my grandmother, from deep inside. It burst like birds from a nest, swoosh and free, a melody clear and sweet. I hoped some day I would laugh like that.

She wiped her eyes. "After that when the border patrolman came by and spent the night, he no longer hung his gun on the porch, he kept it on."

We snapped the last of the green beans. When I heard the cousins come riding back into the farm yard, I smiled secretly to myself. Norma may have gone for the ride, but I had found a Grandma.

The summer Grandpa died, I found a grandma. My father's family planned a reunion at the home ranch and we were going. Finally, I would get to meet my Grandma Lizzy. I saw her a couple of times when I was little, but that didn't count. Both my best friends, Barb and Rose had really neat grandmas and I didn't have any that I knew.

We packed the old chevy full of stuff seven people needed for a four-day weekend and began the two-hundred mile trip east through the Rocky Mountains on a narrow curving road.

We traveled around the Devil's Elbow, across the Continental Divide, down into the Blackfoot Indian Reservation at Browning, then on across the high-line of northern Montana. At Rudyard, we turned north toward the Canadian border and the isolated homestead where Dad was raised.

Norma and I were all excited about going to the ranch and seeing all the cousins. I didn't know I had so many. When we got out of the car, they were everywhere. An amazing amount of people with the bond of blood.

Friendly and outgoing, Norma fit right in with them. I was shy. She was strong, stocky, and dark rich in coloring. I was willowy, dishwater blonde and freckled. She was handsome and I was only ordinary.

The ranch house sat on flat land above deep coolies where the Milk River wound it's way through their bottom separating the ranch from Canada. With a beauty all their own, sage brush, clump grass, and low flat cacti covered the ground, all either tan or brown.

The next morning I overheard Norma and the older cousins planning a horse riding expedition and I wanted to go.

"No," said Norma, "you are way too young to ride the ranch horses." That settled that. Her word was law. I sat by myself on the porch step and watched them ride by laughing and excited as they guided their horse down the narrow trail to the bottom of the coolies.

I went inside and found Grandma Lizzy in her kitchen. This, my only living grandma, was strange to me. She was short, wide and walked with a limp. A hearing-aid poked in her ear had a wire running down inside the neck of her gingham house dress, and she smelled old. I liked her friendly smile.

"I could use someone to chat with," she said. "Sit down and snap those green beans for me." I looked at the dish pan filled with beans and obeyed.

"Grandma Lizzy," I asked as my pile of snapped beans grew on the table, "is it really true you had a hamburger stand?"

"Um-hum."

"Out here on the prairies?"

Her pale blue eyes searched my hazel ones as she nodded.

"Yep," she said, "I did. It was back in '28, '29 and '30 that your grandpa put on a rodeo every forth of July."

"A rodeo?"

"Yep, he invited people from all around. They came by the cars full. Pa had them park in a big circle. That made a nice arena. He provided the bucking horses and steers for roping."

"Why did he do it?"

"To earn cash money." She tilted slightly back on her maple chair. Her face lined with a mole on her chin. It had a coarse center hair. She seemed tired as she continued, "We did everything we could to earn it."

"Tell me about the hamburger stand."

Her eyes twinkled. "First, I'd butcher me a cow, grind the whole thing into hamburger to make patties. I took them to Goldstone on the day of the rodeo, set up my stand next to Warhank's store so I could have electricity for the hot plates"

"Where did you get the stand?"

"The boys made it. The front was open -- you know, like the firecracker stands are. They made it just big enough for me and my cooking things. I sold the hamburgers for twenty-five cents each. I made good cash money, but let me tell you it was hard hot work inside that stand and the horse flies were awful. Sometimes I wonder how I did it."

I looked at that tiny old lady and wondered too, but then her eyes held mine tight and I knew. Those eyes still held the fiestyness of her youth. My dad had the same eyes.

"Who rode the bucking horses?"

"Cow hands and Indians from the Rocky Boy Reservation. Those indians could really ride those bucking broncos. My boys, Donald and Laverne, could ride 'em real good too."

I pushed my pile of snapped beans further into the middle of the table to make room for more. From the dish pan, I poured Grandma Lizzy another lap full and refilled my lap.

"Did you have Fourth of July fireworks for the rodeo?" I picked up another bean with my tired fingers.

"No, we just had bucking horses and drunken Indians."

I blinked. Nobody ever mentioned drunken anything to me before so naturally I asked, "How'd they get drunk?"

"I'm not sure," she said. "Could be that Pa sold them some Canadian beer." She paused and rubbed her nose. "The border patrolman checked on Pa every chance he got to see if he could catch Pa with bootleg beer or whiskey, but he never found it. Every now and then he stopped by when it was late in the day and spend the night. He always hung his gun on the front porch before coming into the house. I always gave him a good supper with a big glass of cold buttermilk. He loved my buttermilk. The next morning he would continue on his way, patrolling the district and snooping in folk's business."

She snapped a few beans while thinking.

"One time he caught your Uncle Cecil pelting beavers and confiscated all twenty of them. That made me darn mad. The hide money would have bought winter shoes for the kids."

Grandma Lizzy's face set in a hard line. "I fed him good, and he paid me back by poking his nose in everywhere. Always checking for bootleg whiskey, then he found them turkeys."

"Turkeys?"

"Thirty dressed turkeys cost Pa his brand new 1936 Ford pickup."

"What?"

"Yep, thirty turkeys caused a great commotion. I told you old man Warhank owned the store in Goldstone?"

I nodded.

"He wanted Pa to pick up thirty dressed turkeys and bring them over the border for him. Warhank wanted to sell them in the store and everything was just fine until that nosy border patrolman happened into the store. He demanded to know where the turkeys came from. We figured Warhank squealed on Pa to get himself off the hook."

"That wasn't very nice," I interrupted.

"No, it wasn't. When the border patrolman showed up at the ranch, he told us he had to confiscate our brand new 1936 Ford pickup, because it transported illegal turkeys. I hit the ceiling. I went out and got in the pickup. I flat told him that nobody was taking my pickup anywhere. I paid seven hundred cash dollars for it, and NOBODY IS TAKING IT ANYWHERE!"

I stared at my grandmother

Fire and anger crackled in her eyes. "The border patrolman ended up with the pickup. Pa ended up with a very mad wife, and old man Warhank ended up Scott free."

A chuckle grew in my grandmother, from deep inside. It burst like birds from a nest, swoosh and free, a melody clear and sweet. I hoped some day I would laugh like that.

She wiped her eyes. "After that when the border patrolman came by and spent the night, he no longer hung his gun on the porch, he kept it on."

We snapped the last of the green beans. When I heard the cousins come riding back into the farm yard, I smiled secretly to myself. Norma may have gone for the ride, but I had found a Grandma.

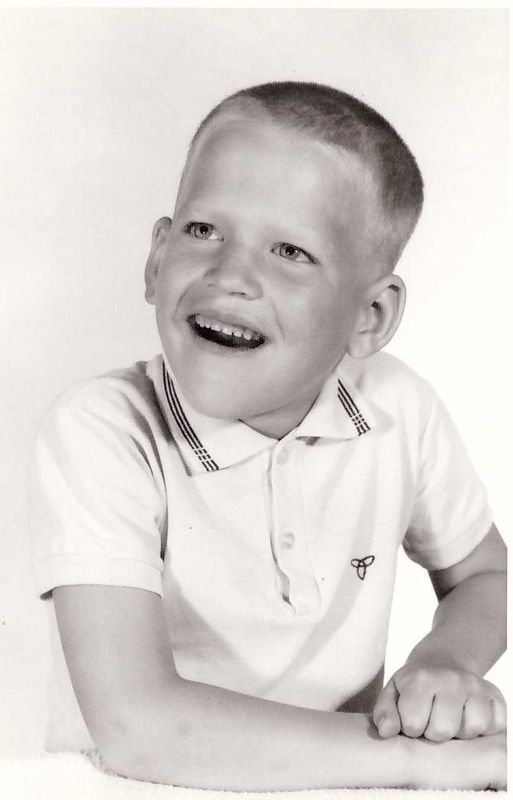

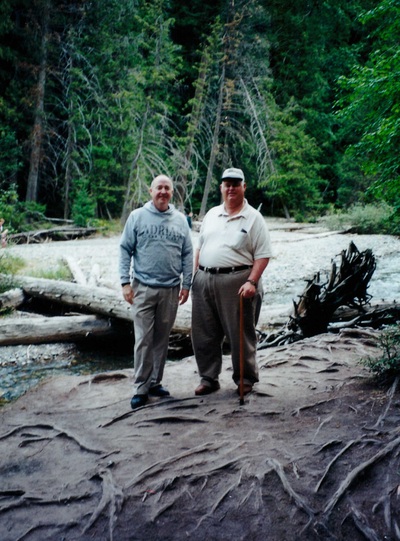

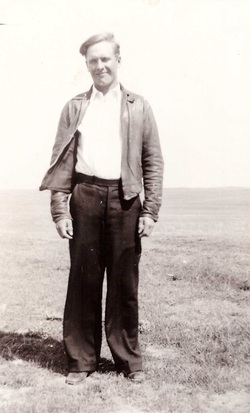

Clarence, the shooter

Clarence, the shooter

Story 9 "The

Shooter"

Our neighborhood changed some. The Grileys moved shortly after Norma lined all of us barefoot kids up and shot each one on the top of their foot with a BB gun to see if it hurt. Grileys sold their house to an old couple. She was dying of cancer. Mom was a good neighbor to them, but us kids ignored them until the evening Mr. McFadden knocked on our door and wanted to talk with Dad.

"Clarence," he said, "you got to do something about those rabbits." His huge frame filled our doorway.

"What rabbits?" asked Dad.

"You know darn good and well what rabbits. You're the one who opened his hutches last fall and turned them loose."

"How do you know I did it?"

"I asked that oldest daughter of yours if she knew how all the rabbits got all over the place." His natural scowl deepened. "She told me you turned them loose because your kids weren't taking care of them like they promised."

Dad drew his five-foot, seven-inch frame to its fullest height. "I'll take care of it," he said.

"You'd better, because my whole shed is undermined. I don't want'em to start on the house. There must be fifty of 'em under there. How many did you turn loose?"

"Only a few. I wanted to butcher them, but the wife said the kids wouldn't eat them. Well, they're going to now."

"Where's Norma?" Dad asked me after he shut the door.

"I don't know," I answered, "but how are you going to catch them?"

"I'm not going to catch them, I'm going to shoot them." He headed toward the kitchen.

"But Dad they sleep all day and only come out at night."

He turned. "Marie, I don't have time for your questions. I'll spotlight them with a flashlight."

My face fell. "That's awful. What if you only wound them."

Dad's frown lessened. He leaned against the doorjamb to the kitchen.

"I won't wound an animal or leave one hurt. At the ranch when I was a boy I learned how to shoot real good. Pa gave us all a particular job. I was the shooter."

"The shooter?"

"Yes, that was my job. Everything that needed shooting I had to do it." Dad scratched his head. "You know like cattle and hogs for butchering." His voice faded a little as he added, "One time I had to shoot a little white horse."

Quiet, I waited for my father to continue.

He seemed to slumped a little against the knotty-pine wall.

"Her name was Cricket. A small little thing for a race horse, but fast, real fast. No horse could beat her."

"Did you race her?"

"Yes, at the rodeos Pa held. She never did get beat. Me and my brothers earned cash money betting on her. One day when Harvey rode her, she stepped into a badger hole and broke her leg. I had to shoot that little white horse." Dad rubbed the side of his jaw. He'd said all he could about shooting and horses.

I watched after him as he walked into the kitchen. I heard him ask Mom, "Where's Norma?"

That night I watched from my upstairs bedroom window as Dad and a couple of neighbor men shined flashlights and shot rabbits. I jerked a little as each shot rang out in the dark. We ate rabbit several times a week for months. I hated it. I was secretly delighted every time I saw a rabbit dart into a bush or under a shed.

At least that one got away.

Our neighborhood changed some. The Grileys moved shortly after Norma lined all of us barefoot kids up and shot each one on the top of their foot with a BB gun to see if it hurt. Grileys sold their house to an old couple. She was dying of cancer. Mom was a good neighbor to them, but us kids ignored them until the evening Mr. McFadden knocked on our door and wanted to talk with Dad.

"Clarence," he said, "you got to do something about those rabbits." His huge frame filled our doorway.

"What rabbits?" asked Dad.

"You know darn good and well what rabbits. You're the one who opened his hutches last fall and turned them loose."

"How do you know I did it?"

"I asked that oldest daughter of yours if she knew how all the rabbits got all over the place." His natural scowl deepened. "She told me you turned them loose because your kids weren't taking care of them like they promised."

Dad drew his five-foot, seven-inch frame to its fullest height. "I'll take care of it," he said.

"You'd better, because my whole shed is undermined. I don't want'em to start on the house. There must be fifty of 'em under there. How many did you turn loose?"

"Only a few. I wanted to butcher them, but the wife said the kids wouldn't eat them. Well, they're going to now."

"Where's Norma?" Dad asked me after he shut the door.

"I don't know," I answered, "but how are you going to catch them?"

"I'm not going to catch them, I'm going to shoot them." He headed toward the kitchen.

"But Dad they sleep all day and only come out at night."

He turned. "Marie, I don't have time for your questions. I'll spotlight them with a flashlight."

My face fell. "That's awful. What if you only wound them."

Dad's frown lessened. He leaned against the doorjamb to the kitchen.

"I won't wound an animal or leave one hurt. At the ranch when I was a boy I learned how to shoot real good. Pa gave us all a particular job. I was the shooter."

"The shooter?"

"Yes, that was my job. Everything that needed shooting I had to do it." Dad scratched his head. "You know like cattle and hogs for butchering." His voice faded a little as he added, "One time I had to shoot a little white horse."

Quiet, I waited for my father to continue.

He seemed to slumped a little against the knotty-pine wall.

"Her name was Cricket. A small little thing for a race horse, but fast, real fast. No horse could beat her."

"Did you race her?"

"Yes, at the rodeos Pa held. She never did get beat. Me and my brothers earned cash money betting on her. One day when Harvey rode her, she stepped into a badger hole and broke her leg. I had to shoot that little white horse." Dad rubbed the side of his jaw. He'd said all he could about shooting and horses.

I watched after him as he walked into the kitchen. I heard him ask Mom, "Where's Norma?"

That night I watched from my upstairs bedroom window as Dad and a couple of neighbor men shined flashlights and shot rabbits. I jerked a little as each shot rang out in the dark. We ate rabbit several times a week for months. I hated it. I was secretly delighted every time I saw a rabbit dart into a bush or under a shed.

At least that one got away.

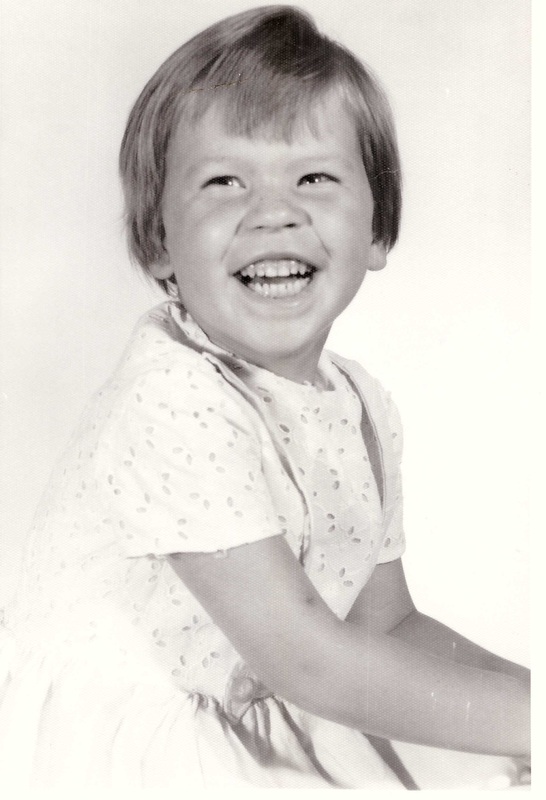

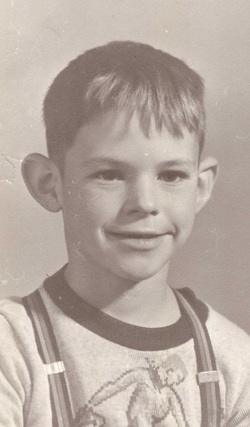

Alan

Alan

Story 10 Butterhead

My younger brothers and sister started to become people. Alan, the oldest, grew strong and agile. Norma now allowed him to play with us--if we needed him. She loved baseball and let Alan fill a place in right field when we played pasture baseball with the local boys. She pitched and hit with the best of them.

Alan even got to fish with us now. He dug fishing worms with great ease and he could also carry lumber for our forts. Why he wanted to play with us, I'll never know. He must have felt like an abused child and not only from Norma and me, but our mother.

One day, Mom stood at the kitchen cupboard, squeezing a plastic bag of margarine. The red-orange dye slowly worked through the white Oleo making it yellow.

Alan trooped through the kitchen on his way outside. As he went by, Mom playfully reached out and tapped the top of his head with the margarine bag. To Mom's surprise, it split. Alan stood there with orange and yellow streaked Oleo running down his head. After that his name became Butter-Head Alan anytime Norma was aggravated with him.

My younger brothers and sister started to become people. Alan, the oldest, grew strong and agile. Norma now allowed him to play with us--if we needed him. She loved baseball and let Alan fill a place in right field when we played pasture baseball with the local boys. She pitched and hit with the best of them.

Alan even got to fish with us now. He dug fishing worms with great ease and he could also carry lumber for our forts. Why he wanted to play with us, I'll never know. He must have felt like an abused child and not only from Norma and me, but our mother.

One day, Mom stood at the kitchen cupboard, squeezing a plastic bag of margarine. The red-orange dye slowly worked through the white Oleo making it yellow.

Alan trooped through the kitchen on his way outside. As he went by, Mom playfully reached out and tapped the top of his head with the margarine bag. To Mom's surprise, it split. Alan stood there with orange and yellow streaked Oleo running down his head. After that his name became Butter-Head Alan anytime Norma was aggravated with him.

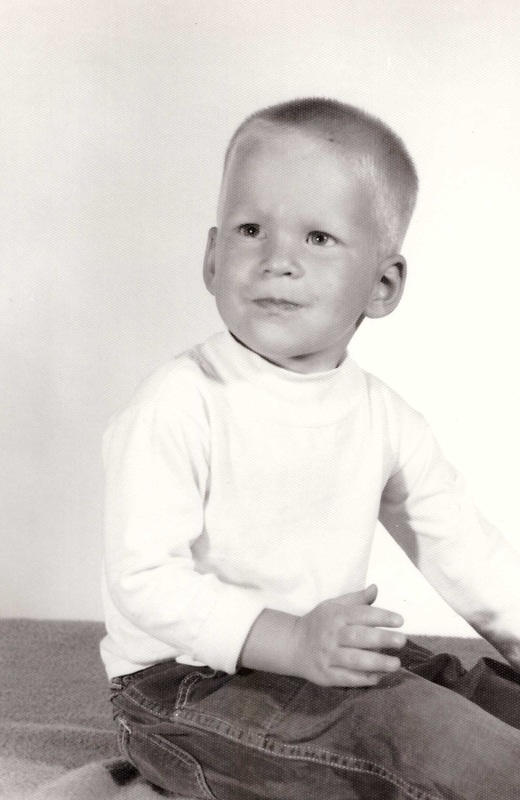

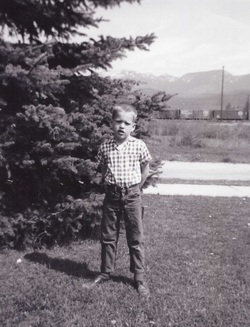

Doris and Dave

Doris and Dave

Story 11 Sassy Mouth

Dad sold the acre of land between us and McFadden's to the Wilsons. Pearl and her husband built a garage and lived in it while they built a house. Their two girls were the same age as my little sister, Doris, and my littlest brother, David. The four of them became instant buddies.

Pearl, a tall rawboned woman, became my mother's great coffee friend. As they sat at each other's kitchen tables, they shared not only coffee, but recipes, gossip, small talk and comfort.

Pearl was kind and loving, but very defensive where her girls were concerned. If anyone picked on them, her temper blazed red hot. Us kids called her Spitfire Pearl.

The summer she was pregnant with her third daughter, the temperature soared. Pearl's temper soared right along with it.

One day while Norma ironed and I washed dishes, the front door flew open with a bang. We heard hard-running feet. Doris and Davy flew through the living room, then the dining room, then by Norma at the ironing board, past me at the sink and then with a great slam, out the back door they went!

Hot on their heels was Pearl with a stick!

Norma stared at me with arched eyebrows. "Wonder what sin they committed?"

I shrugged. "Don't know."

"I'm going to find out." Norma headed for the door. I was hot on her heels.

Pearl had Doris and Davy cornered out by a shed. She stood there with her chest heaving and her frumpy house dress pulled tight across her pregnant stomach. Her long knobby-kneed legs were planted wide. She shook the stick at Doris.

"What did they do?" Brave Norma asked.

Pearl turned. "Doris told me I couldn't do anything about her teasing my girls." She turned back to mute, frightened Doris. "You still think I can't do anything?"

Doris shook her head hard enough that her pigtails bounced back and forth slapping her in the face.

"I'll take care of Doris' sassy mouth, Pearl," said Norma.

"You'd better, or next time I'll use this stick."

Norma drew to a bigger height. She pinpointed Pearl's eyes. They stood glaring at each another. Pearl went home. Norma grabbed Doris by the arm and drug her inside.

Later Doris told me she liked the taste of soap.

Story 12 Shorty pajammas

By mid August, the summer between my seventh and eighth grade was hot. Scorching dry, hazy days settled over our northern Montana valley. Lakes warmed to a good swimming temperature and our upstairs bedrooms were hot with a Capitol "H".

Norma came up with an exciting plan. We approached Mom.

"Mom, can we have a pajama party in the clump of trees?" asked Norma.

"Who's we?" asked Mom as she kneaded a large batch of bread on the counter.

"Naomi, Florine, Carol, Rose, Janet, Barbara, Marie and me," answered Norma. Pausing for a breath, she continued, "It would be so much fun. They could all bring their sleeping bags, and we could have a picnic supper out there, and we wouldn't be any trouble at all. Can we, Mom, can we? It's so hot upstairs."

Mom poked her fingers deep into the dough and pushed forward. A stray lock of premature gray hair slipped across her eye glasses. She pushed it back avoiding the flour on her hand and turned to us with a weary sigh.

"It is too hot to be baking bread let alone have a house full of your friends,"

"But, Mom," pleaded Norma, "I said we'd stay out in the clump of trees. We wouldn't bother you. Marie and I will cook supper and everything."

I nodded in agreement.

Always the patsie, Mom smiled. "Oh, all right. I guess it won't hurt anything."

Our clump of trees was a small stand of Bull Pine and Spruce located almost at the rear of our ten acres. Norma and I spent the afternoon raking long dry needles into eight mattresses for our sleeping bags. Then we fixed sandwiches and pork and beans and potato chips and some of Mom's fresh cinnamon rolls for supper. We carted the food and sleeping bags out to the trees. Finally we were ready.

"Man, this has been a lot of work," I said as I wiped perspiration from my forehead.

"Yeah," Norma agreed, "but it's worth it. We'll have a blast. I can hardly wait for everyone to get here."

"Me, too."

Norma glanced at the sun in the western part of the sky. "They'll start showing up pretty soon. You know, we ought to plan some games for tonight."

"Okay, what games?"

"I was thinking of a snipe hunt at the cemetery. Come on let's go plan our route." We scooted under the barbed-wire fence that separated our land from the Saddle Club, skirted around the grandstand, then entered the cemetery at the back. While Norma plotted where we'd lead our friends, I walked farther in toward Grandpa's grave.

"Hey, look here," I called when I saw a big pile of dirt. "They must have dug a grave."

Norma wandered over.

We stared down into the empty grave.

"Looks deep," she said.

"Yeah," I agreed. "It gives me the creeps."

Norma walked around the grave. Her dark hair glistened in the sun. Her dark brown eyes gleamed with excitement. "You know what?" she asked.

"What?"

"I could get an old sheet and hide in here tonight." She kicked a clod of dirt with her toe and it fell into the hole. "You could bring the girls for the snipe hunt, and I could rise up like a ghost and scare'em." Norma laughed gleefully. "That would be fun, huh?"

"Are you sure you could do it?" My mind saw possibilities.

"Why not? It's just a dumb hole in the ground." She kicked another clod down into the gaping space.

I watched it gather a few more clods as it rolled down the side. Goose bumps made the hair on my arms rise. "How will you get over here without them knowing?"

Norma scratched behind her ear. "I know, I'll say I have to go to the house for something, then I'll slip around and come in by the highway."

"Okay," I agreed with a smile teasing my lips. The picture of Norma coming up out of that hole brought silent laughter to my mind. I figured that maybe there could be some way to turn this into a good joke on Norma, if I could pull it off.

We went home, got an old sheet and hid it in the shed for a quick pick up by Norma. Then we gathered brown paper bags for the snipes. I slipped a phone call to my bosom buddy, Barbie.

Our friends arrived on their bikes, each carried a sleeping bag in their baskets. Our party began. At the point of almost total darkness, Norma headed to the house with the excuse that Mom needed her for a bit.

"Over on the other side of the Saddle Club grounds are snipes," I explained to Rose, Janet, Naomi, Florine, Carol and Barbie who were sitting on their sleeping bags in their shortie pajamas.

"What's a snipe?" asked Rose.

"They're these little things that only come out at night. They're lots of fun to catch. Do you guys want to try to catch some?"

"It sounds like a blast," said Barbie with a giggle. I looked at her and gave a slight wink.

"Well," said Rose, "I don't want to catch something that I don't know what it is I'm catching."

"I can't describe one," I said. "You'll have to catch one and look inside to see what it is. They are real neat. I just love them."

"I do, too." Barbie's giggle was getting worse. I gave her a shutup look.

"I don't believe there is such a thing," said Naomi.

"Well, seeing is believing and you can't see one unless you catch it first." I can be a convincing innocent person when I want to. They all agreed we should go.

The clear black sky filled with starlight, just enough for us to see each other and where we were going. I herded them under our fence, around the grandstand, across a narrow pasture and to the cemetery fence.

"Come on," I said, "we'll cross under down there by the wild rosebushes."

"Why down there?" asked Rose.

"Because there is a little dip in the ground. It'll be easier to crawl under the barbed wire." And Barbie could slip around to the back without Norma seeing her, I thought, chuckling. I reached down and pulled on the wire as Naomi, Florine, Carol and Barbie crawled under, but this is where Rose drew the line.

"Marie, there ain't no way I'm going into that cemetery," she said.

In the starlight I saw her ruffled shortie pajamas bounce as she shook her finger.

"But you gotta," I said. "That's where the snipes are at."

"For cripes sake, Rose," said Barbie, my ally, "you're such a chicken."

"I am not and I'm not dumb either and this is dumb. It's just plain stupid to go into that cemetery at this time of night."

"Okay," I said, "if you want to stay here by yourself that's all right with me." I scooted under the fence scratching my knees on the dry alfalfa.

"Wait a minute," cried Rose, "I'm coming." I could hear her grunt with the effort of crawling under the fence.

"Shh," I said, "we all have to be quiet or we'll never catch any snipes. Has everybody still got their bags?"

"Yes," said Rose, "where do you think they'd be?"

My fingers itched with a need to choke her, but instead I whispered, "Hold your bags open and close to the ground. Be deathly quiet." I led the way. We slipped past the big Talbott tombstone and on across the cemetery. At my discreet signal, Barbie separated from us and stole behind where Norma waited in the hole.

"What's that," whispered Rose?

"What?" asked Naomi.

"Over there." Rose grabbed her by the arm, pointing.

We stared in the direction she indicated. A light shadow rose slowly from the ground. It stood swaying by a black hump. A low eerie wail emitted from it. I knew it was Norma, but hackles rose on my neck anyway. Suddenly a black form flung itself at the light shadow. I heard a thump and a cry and a grunt and a scream. Six girls screamed in bloodcurdling unison. The screech deafened.

We sprinted pel-mel through the cemetery, past the dark shape of the grandstand, by the clump of trees and toward my house. Rose's scream never quit. It was a mournful wail at a high soprano pitch that joggled as she ran hell bent for the beacon of light coming through the living room window.

Mom and Dad came running out of the house. Mom grabbed Rose as she flew past and held her by the shoulders.

"Stop it, Rose," she ordered.

Rose's scream reduced to crying and sobbing.

Mom's glare found me in the window light.

"What happened?" she demanded.

"There's a ghost in the cemetery," gasped Naomi.

"Mom, there really is," said Norma as she entered the dim light beam. "But it's okay now. It tried to knock me into the grave hole, but I knocked it in instead. It put up quite a struggle, but I finally managed to push it in."

"That was Barbie, you idiot," I whispered. "Where is she now?"

Norma shrugged. "What's the matter with everybody?" she asked. "It was just me and Barbie for crying out loud."

"Everyone into the house," ordered Dad.

Mom called Rose's mother to come get her hysterical daughter.

I went to find Barbie who refused to speak to me and followed mutely back to the house.

Rose's folks came. As they led Rose out the door, she turned to us. "I'll never stay at your house again," she announced, then as she climbed into their car her bottom lip spat out, "EVER!"

The next morning after a night spent on the living room floor, our friends rolled up their sleeping bags and threw them into their bike baskets and pedaled for home.

"Thou shalt be grounded even after death," Mother said to Norma and me.

Story 13 I Got Married

The summer of my sixteenth year was a major turning point. Norma left, and I met Elmer.

Norma graduated from high school and moved to Alaska with Naomi's family to seek her fortune. Her leaving left a considerable hole in our family. I couldn't believe I missed her. I had waited all my life for the day Norma left. Now with her gone the house seemed empty. I had no one to share the household chores or to fight with. Doris was old enough to help, but she was a sly little thing and managed to worm her way out of dishes and ironing.

My two best friends were Barbie and Rose. Both had forgiven me for the snipe hunt after I explained it was all Norma's fault. We spent every hour we could together.

Barbie's father allowed her to use his old 1948 drab olive-green Nash. It was a big clumsy car with a sloping back and lots of chrome. Where ever we went it always brought admiring comments from guys. Their interest provided us with a continuing supply of possible boyfriends.

Early one summer night, Barbie telephoned. "I just talked to Rose and she thinks we ought to go to the drive-in."

"What's playing?"

"Who cares? It's a nice night and my father said we could use the Nash. Want to go?"

"Sure," I answered. "What are you wearing?"

"My white pedal pushers. What else?"

On her way to my house, Barb picked up Rose. By the time they came for me the sun had disappeared behind Dollar Hill. The evening star was visible in the last sun rays as we drove west on Highway 40.

The drive-in theater sat on the north side of a four-corner intersection behind a tall woven-board fence of a drabber green than the Nash.

It took Barbie several tries before she parked the Nash perfectly on the mound by a metal speaker post. The night became blacker as we ate homemade popcorn while waiting for the show to start. The floodlights turned off. The screen filled with previews of coming attractions.

At intermission, the real show for us girls began. Different sets of guys began making their way to the snack bar. Some paused and waved as they passed by, others stopped for a good look at the faithful old Nash.

A threesome of guys wandered by. They paused to gaze in the floodlights at the gleaming chrome. I recognized two of them as classmates. We asked them if they wanted to sit in the back and talk for a while.

They introduced Elmer to us and that was it. I was a goner. I kept stealing quick peeks at him in the muted light from the large screen. Every time our eyes connected and he smiled I melted more. He was blonde and blue-eyed with bulging healthy nineteen-year-old muscles. His rough and tumble attitude seemed very mature.

The next day he called and my life began. Everything before Elmer ceased to be. He took over my every thought and feeling. Nothing mattered but to be with him and I was lost to a world of passion.

"You are entirely too young," said Mom when I explained we wanted to get married, she snuffed in her breath. Dad wouldn't even speak to me. Finally by January they agreed to a wedding.

We were married in the middle of winter. I was sixteen and Elmer was nineteen--so young, but we didn't think so. We rented a tiny two-room apartment in Columbia Falls and moved in after the small wedding.

Pastor Warner married us in my parents living room with family and a few friends. Some of Elmer's relatives were still in Montana and they came, Pearl from next door and of course Barbie and Rose.

The ceremony was nice, anyway I guess it was. I can't remember. I think I was too scared to remember. The wedding scared Elmer, too. In our snapshot-wedding photo he looks dead drunk, but he wasn't, just petrified out of his wits.

Story 14 Grown-up

After setting up house, the first thing I learned was how to make a good cup of coffee and how to inhale cigarettes. These two became constant companions and pulled me through times I needed solace. My choice of drugs.

We had absolutely no idea how to make a marriage work, only finding out after years spent together and many battles. Battles of the immature are terrible. Each thinks they are all grown up and have all the answers like the time Elmer insisted, "I can beat you at Aggravation anytime I want to."

"I don't think so," I answered with an amused chuckle.

"You think you're so smart. Get out the board."

I brought out the homemade board. Elmer had carefully drilled holes for the marbles to sit in and sanded the plywood smooth. We played every evening after his smart-aleck challenge with me consistently winning and laughing.

The more I won the more aggravated Elmer became until past the point of control he tossed the board, marbles and almost me out the door. His fury frightened me. I had never seen anyone that angry over nothing or for that matter something. Our marriage survived the Aggravation game with me learning to keep my mouth shut. We were definitely all grown up and ready for marriage and a baby.

My baby conceived in my passion, born of my blood, died. It is still surreal to me. He was born premature after months spent in bed trying to protect him. I never saw my baby, only a glimpse when a nurse rushed by the delivery table carrying him somewhere. Then they gave me ether.

Later the doctor came. "Your baby died," he whispered in my ear. "I hand pumped air for over an hour, but his lungs were unable to breathe on their own." I could tell he was crying and all I could do was nod.

Elmer came in. We cried together. They had the funeral while I was in the hospital. I stood under Grandpa's bull pine tree and stared my baby's grave on the opposite side of the tree trunk from Grandpa.

"Goodby," I whispered, "Grandpa will take care of you." I knelt down, patted some of the sandy soil into a small mound and built a little dry pine needle house, then left the cemetery arm in arm with Elmer.

Eighteen months later I held my brand new baby Danny in my arms. I tried to nurse him and it hurt.

"This really hurts," I said, glancing at the nurse.